By Nura Kabale

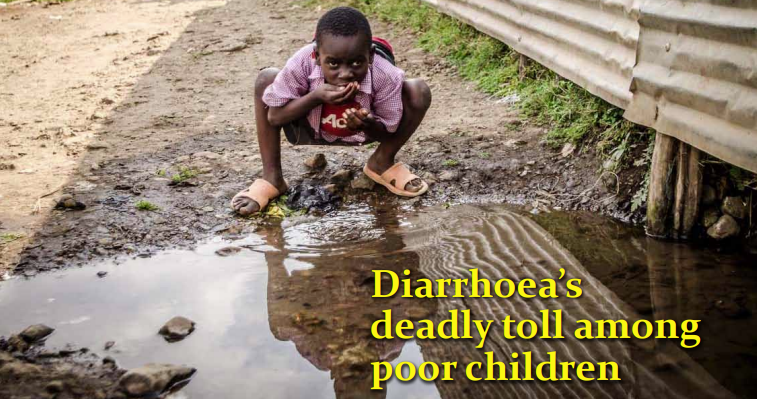

Poverty renders thousands of children in Kenya vulnerable to death from preventable diseases, a new study shows. A recent study by Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) and Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) that was conducted in Kakamega, Bungoma and Vihiga Counties between 2012 and 2014 shows correlation between poverty and diarrhoea.

The joint research indicates that high rates of poverty in Western Kenya undermine efforts to curb prevalence of killer diarrhoea among children in the region. Most poor families, the research found, ignore basic household hygiene standards making children suffer from diarrhoea. Findings reveal that interventions, including use of treated water, proper human waste disposal and hand washing by mothers and child care-givers, did not stop the prevalence of diarrhoea in the counties.

On average, cases of diarrhoea were over 70 per cent of the total children in the first and second year of study. For example, in the first control group involving 1394 mothers, the children that experienced diarrhoea were 1,394 in the first year and 1,511 in the subsequent year. According to World Health Organisation (WHO), diarrhoea is the second leading cause of death among children below the age of five.

WHO notes that the disease can be prevented through use of safe drinking water and adequate sanitation. “None of the interventions reduced diarrhoea prevalence compared with active control,” said IPA lead researcher Clair Null during the release of the report. Primary outcomes indicate that mothers reported diarrhoea in the first seven months after the intervention was done.

While interpreting the report, Null decried mothers’ non-adherence to hygienic standards. “Poverty makes it difficult for people to focus on preventive measures. They are busy taking care of the elderly, looking for fees and other basic needs,” said Dr Null. The study, which involved 8,246 women from pregnancy and past delivery, showed that the socio-economic environment could not support the realisation of preventive measures.

For example, lack of accessible water compelled women to go for water at different points and hardly have time to treat it. “We need to make it easier by making water accessible to all if the approach would be geared towards success,” Null recommended.

Even when women cleaned their hands after using latrines, the effort was futile because soil samples in home compounds and gardens tested positive for pathogens and intestinal worms. Further, the research connects laxity to observe intervention measures to cases of stunted growth among children in the region. The finding confirms the statement by WHO that diarrhoea causes malnutrition in children under the age of five.

Sammy Njenga, a researcher at KEMRI, said there was slight reduction in intestinal worm infestation among children due to use of clean water and hygiene. However, use of active intervention of drug administration was more efficient. He said there was a danger that the parasites would develop drug resistance with the frequent use of medicine and thus the use of interventions was advised.