Giving the hormone progesterone to women who have had a miscarriage and experience early bleeding in pregnancy could improve their chances of having baby, a study suggests.

Birmingham researchers carried out a trial on 4,000 pregnant women.

Samantha Allen, 31, experienced spotting when she lost her first baby and then again during her second pregnancy.

After taking the hormone for eight weeks, she gave birth to her son Noah.

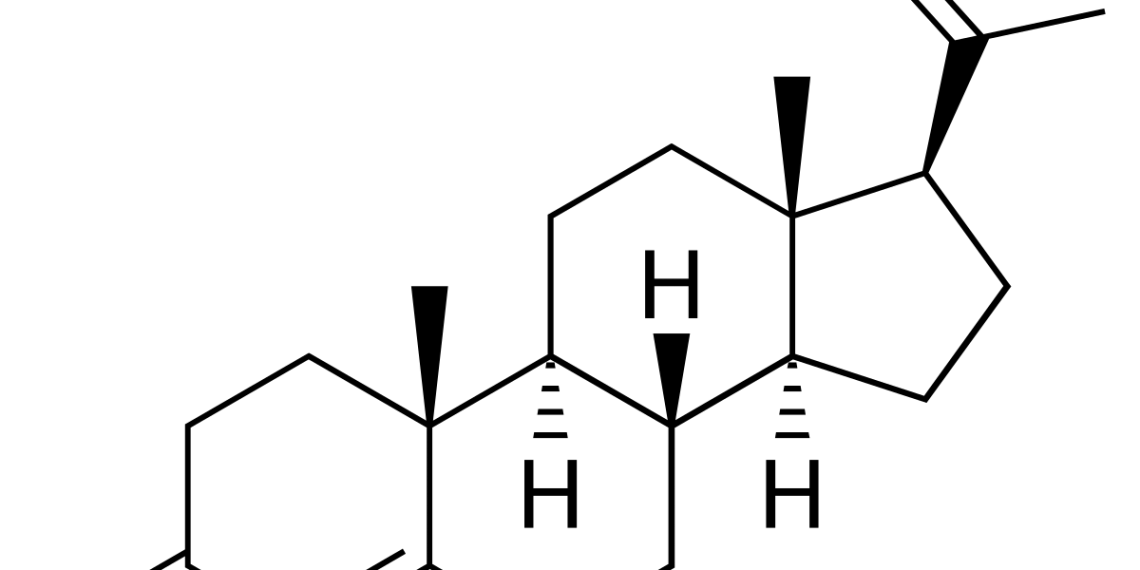

Progesterone is a hormone essential in pregnancy – for maintaining the lining of the womb where the embryo is implanted and for supporting the immune system.

Samantha was prescribed progesterone pessaries for the trial, which she took twice a day until she was 16 weeks’ pregnant.

She said the bleeding stopped within a week of starting the trial and the pregnancy progressed very smoothly.

She now hopes that more women who have had a miscarriage could benefit.

“I just hope they don’t have to go through the same heartache – it does take its toll on you,” she said.

Miscarriage affects one in five women, and vaginal bleeding in early pregnancy is linked to an increased risk of it happening.

With progesterone already used in IVF treatment, Samantha said that she had no qualms about taking part in the trial.

“I feel happy that I did participate. It didn’t feel like a risk because it wasn’t an early stage trial.”

The University of Birmingham study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine,involved one group of around 2,000 pregnant women given progesterone, while another group of the same number were given a placebo, or dummy pill.

All the women had experienced bleeding in early pregnancy.

Although the study showed that not all women with early bleeding could be helped by taking the hormone, the benefits were greatest among women with a history of recurrent miscarriages (three or more).

Among those women, there was a 15% increase in the live birth rate – with 98 out of 137 women going on to have a baby, compared with 85 out of 148 in the placebo group.

Arri Coomarasamy, study leader and consultant gynaecologist at Birmingham Women and Children’s Hospital, said the treatment could save thousands of babies’ lives.

“We hope that this evidence will be considered by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and that it will be used to update national guidelines for women at risk of miscarriage,” he said.

At present, when women are potentially miscarrying, “there is nothing we can offer them”, he says.

But he said that the treatment would not work for all women who miscarry, because there were many complex reasons why miscarriage occurs.

Only those women with a progesterone-related problem could benefit, he added.

Jane Brewin, chief executive of miscarriage charity Tommy’s, said: “The results from this study are important for parents who have experienced miscarriage; they now have a robust and effective treatment option which will save many lives and prevent much heartache.

“It gives us confidence to believe that further research will yield more treatments and ultimately make many more miscarriages preventable.”

-BBC