Cuba has long been renowned for its medical diplomacy – thousands of its doctors work in healthcare missions around the world, earning the country billions of dollars in cash. But according to a new report, some of the doctors themselves say conditions can be nightmarish – controlled by minders, subject to a curfew and posted to extremely dangerous places, James Badcock reports.

For Dayli Coro, medicine was a calling.

“I studied medicine out of vocation. I used to sleep between three and four hours because I studied so hard. I worked hard in my first year of practice, I took on a lot of extra shifts. And now here I am. I cannot be a doctor in Cuba. It’s very frustrating.”

Dayli, now 31 years old, wanted to be an intensive care specialist. She says that after graduating, she was told that if she went on a medical mission to Venezuela, she would gain experience in her chosen field and that it would count as her three years of obligatory social service, which all graduates have to complete in Cuba before gaining full-status posts.

She agreed to join what Havana calls its “internationalist missions”, following a path trodden by hundreds of thousands of Cuban doctors. Since 1960, their medical work overseas has been held up by the communist government as a symbol of its solidarity with people all over the world. Fidel Castro described the medics as Cuba’s “army of white coats”.

As well as a source of great pride and prestige, it is also an economic lifeline for the regime. According to Cuban government figures and academic studies, the scheme earns Cuba around $8 billion per year in much-needed foreign currency.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESWith more than 30,000 Cuban doctors currently active in 67 countries – many in Latin America and Africa, but also European nations including Portugal and Italy – Cuba’s authorities draw up strict rules in an attempt to prevent citizens defecting once abroad.

The wages on offer were another strong incentive for Dayli, who is originally from the small Cuban city of Camagüey, to join up. Going from a doctor’s salary on the island of just $15 a month in 2011, she says she was paid $125 monthly for the first six months in Venezuela, a figure that rose to $250 after six months and $325 during her third year. Her family in Cuba also received a bonus of $50 a month.

According to a report by Prisoners Defenders, a Spain-based NGO that campaigns for human rights in Cuba and is linked to the Patriotic Union of Cuba (UNPACU) opposition group, doctors on average receive between 10% and 25% of the salary paid by the host countries, with the rest being kept by Cuba’s authorities.

Dayli says she voluntarily signed a contract for a three-year stint, but she neither had time to read it, nor was she given a personal copy.

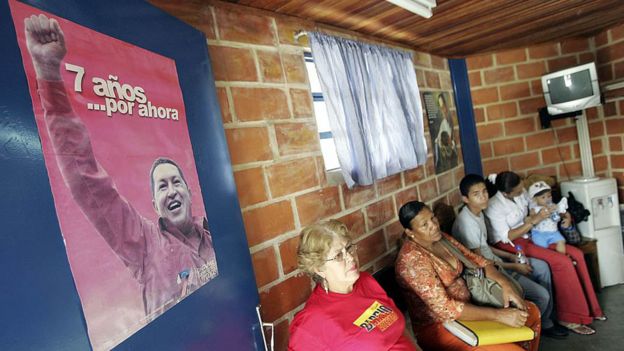

In October 2011, the young doctor was posted to a clinic in the Venezuelan town of El Sombrero. The placement was part of the Barrio Adentro (Inside the Neighbourhood) scheme, which has distributed Cuban doctors around disadvantaged parts of the South American country since 2003 as a symbol of Cuban support for the regime of the late President Hugo Chávez and his successor, Nicolás Maduro. Venezuela pays for this and other services by Cuban workers with oil.

Dayli says she found herself in a virtual war zone – one in which she became accustomed to having a gun pointed at her.

Venezuela was at that time in the midst of a crime rate spiral that has led to a murder rate of 92 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2016, according to the NGO Venezuelan Observatory of Violence. World Bank figures put the 2016 figure at 56 per 100,000, topped only by El Salvador and Honduras.

“There were many criminal gangs,” says Dayli. “When they fought, they brought their injured to us, because the local Venezuelan hospital had a police presence, and we didn’t. These kids would bring in a patient with 12 or 15 bullets in his body, point their guns at you and say you had to save him. If he died, you would die. That kind of thing happened on a daily basis. It was routine.”

The gang members she treated were often just teenagers of 15 and 16, she says.

“I had one with a bullet through the heart, another with five in the head. Some would be alive but you knew that if they were not operated on in 20 minutes, they would die, and we didn’t have the necessary conditions. We didn’t even have basic medicine to treat patients there. There were supposed to be four intensive care doctors, and normally there was only one on shift.”

These patients would often be transferred by ambulance to a general hospital 45 minutes away. Sometimes the gang members would order Dayli to get in the ambulance with them, she says.

“Once an ambulance was shot up by another gang and a Venezuelan doctor and the driver were killed,” Dayli adds. “There was always the possibility that the rival gang might try to finish off the patient during the transfer. I had a situation where a rival gang came in and shot the patient dead.

“I was 24, a tiny, skinny girl. But in a place where there is so much violence, you develop an incredible emotional coldness.”

The medical missions came under the spotlight following decision towithdraw Cuban doctors from Brazilin the wake of President Jair Bolsonaro’s election last year. Bolsonaro questioned the qualifications of the Cuban doctors in the country and described their contractual situation as “slave labour”, pointing out that they only kept 25% of the pay with the rest going to the Cuban government. In response, Cuban authorities strongly rejected the characterisation and said it was “not acceptable to question the dignity, professionalism and altruism” of its international medical staff.

Doctor’s orders?

According to a report by the opposition-linkedCuban Prisoners Defenders, based on direct testimony from 46 doctors with experience of overseas medical missions, plus public-source information from statements by 64 other medics:

- 89% said they had no prior knowledge of where they would be posted within a particular country

- 41% said their passport was removed from them by a Cuban official on arrival in the host country

- 91% said they were watched over by Cuban security officials while on their mission, and the same percentage reported being asked to pass on information about colleagues to security officials

- 57% said they did not volunteer to join a mission, but felt obliged to do so, while 39% said they felt strongly pressured to serve abroad.

The BBC made repeated requests for a response from the Cuban government but received no reply. However, Havana has continued to strongly defend the programme. Cuban President Miguel Díaz-Canel offered his support for “the heroes of Cuban and Latin American medicine” to mark Latin American Medicine Day last December.

“To those who fight for life, it is all the same in a modest Cuban neighbourhood or a village in the Amazon. More than doctors, they are guardians of human virtue,” Cuba’s leader tweeted.

While Dayli at least managed to escape becoming a victim of violence in Venezuela, a compatriot and fellow woman medic was less fortunate. The 48-year-old family doctor wishes to be identified by the pseudonym “Julia” to spare her family knowledge of her ordeal.

During her five-year mission in Venezuela, Julia was stationed in Bolívar state. “I was unfortunate in that the mission co-ordinator took a shine to me, and I didn’t agree to his repulsive insinuations. He had me sent away to a series of out-of-the-way locations in rural areas.”

At one point, along with another Cuban woman doctor, she was posted to a shack with a clear plastic roof. One day when they saw a door had been forced open, they called the co-ordinator – but Julia says he did nothing.

Then, she says, “I woke up one night, with someone holding my mouth shut. The doctor in the other room was screaming. There were two men in balaclavas, armed with guns.” Julia says she was raped by both men.

The mission co-ordinator came to take the two women away from this location, but, Julia says, he suffered no apparent consequences or official reprimand for having exposed members of his team to such danger.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESJulia was taken to Caracas where she was given anti-HIV medicine and sessions with a Cuban psychologist. “Her treatment was not the best. The focus was basically ‘Don’t tell anyone this has happened.'”

While on a mission in Bolivia, Julia defected across the border into Chile, and now lives in Spain, where she has asked for asylum and works as a surgeon’s assistant.

María (not her real name) is another female Cuban medic who says her gender made her a target. She was a 26-year-old family doctor when she was deployed to Guatemala on her first international mission in 2009.

During her journey into the state of Alta Verapaz, the mission co-ordinator began telling her about a rich man in the area, whom he referred to as an “engineer”. Maria says: “He insinuated that he liked Cuban women.” She says she was given a mobile phone, on which the “engineer” began calling her every day.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES“I didn’t answer, and I even changed the number, but still he called,” Maria says. “The co-ordinator told me I would be sent home as a punishment if I didn’t got to see this man, and I said that was fine with me.

“My principles were on the line. I went with the idea of helping poor people on a mission for my country. It was so frustrating – I felt scared but could not run away.” María says that her passport was taken from her by her Cuban minders as soon as she arrived in Guatemala.

After two months of resisting pressure to see the man, María was switched to another mission. Some months later she heard that the “engineer” had been arrested in an army raid, accused of being a drug trafficker. María completed two years in Guatemala, and later absconded from her next mission in Brazil by signing up to a US medical parole program, aimed at persuading Cuban doctors to defect.

Dayli says she and her team in Venezuela had to meet weekly targets set by the Cuban mission leaders related to the number of lives saved, patients admitted and treatments for certain conditions.

She says she rejected what she considered unethical interference in honest medical care principles: “That is where my problems began because I wasn’t going to lie. If a patient is ready to go home and take medicine orally, I am not going to have them admitted for five days on a drip. I can’t say how many heart attack patients I am going to have in a given week.”

According to the Prisoners Defenders report, more than half of 46 doctors with experience of overseas missions who were interviewed reported having to falsify statistics – inventing patients, patient visits and pathologies that did not exist. By exaggerating the missions’ efficacy, the Cuban authorities can, the report says, demand greater levels of payment from the host country, or justify the enlargement of the operation.

Dayli says the conflict she had with her senior medical colleagues at El Sombrero over the instructions to boost treatment statistics led to her being posted in lower-level destination in the calmer, more rural town of San José de Guaribe. But the twin pressures of working without sufficient medical equipment and orders to hit artificial or impossible targets remained.

Once a woman arrived mid-labour, Dayli recalls, but the clinic did not have the right set of instruments for delivering a baby. Another time, she says she had to inset a tube into a patient by the light of her phone as there was no fuel for the generator.

She alleges her request to transfer a man with lung cancer to Caracas was denied so he would count towards her clinic’s statistics.

“The health of Venezuelans is not important to the mission,” she says. “I had an 11-year-old die in my arms when I was trying to put him on a breathing apparatus that was not working.”

Carlos Moisés Ávila tells a similar story. The 48-year-old doctor joined one of the first missions in Venezuela in 2004.

“We each had to report a life saved every day, so sometimes I had to grab someone who was healthy and stick them on a drip,” Carlos says.

“Medicines arrived from Cuba out of date, so we had to destroy and bury them before including them in the inventory as used so they could be charged for. We would get our pay from soldiers, who were sometimes months late in coming, and would also take medicines from the hospital,” recalls Carlos.

Carlos says he signed up for the medical mission to improve his financial situation. Instead of getting around $20 a month in Cuba at that time, he started earning $300 in Brión, in Venezuela’s Miranda province, although he says that the Cuban government was paid more than 10 times that amount for each doctor on the Barrio Adentro programme.

Dayli says that all fraternising with Venezuelans outside of work was prohibited. The Cuban doctors lived together and had to respect a 6pm curfew. The mission co-ordinator was a Cuban security service official.

“He would ask you about your roommates in weekly interviews,” Dayli says. “He had network of paid local informers who would pass on any information about you in order to detect possible deserters. We weren’t allowed to have a drink with a Venezuelan, or go to their house because you saved their life and to see how they’re doing. If you fraternised with a dissident, you could have your mission revoked.”

Carlos says during the seven years he spent in Venezuela, he saw the way medicine was used as a political tool for propaganda purposes, sometimes at the expense of physicians’ ethical code.

“During the 2004 campaign for the recall referendum, we doctors were sent out door to door to give out gifts and medicines to boost support for President [Hugo] Chávez,” he says. “We also had lists of patients according to their political tendencies. Chávez regime supporters were put down as having hypertension, while opposition people were listed as diabetics. The former got better treatment, and any information we gathered on locals was passed on to the mission co-ordinator, a Cuban woman who controlled all of our personal relationships and who we were allowed to meet.”

A New York Times report in March quoted Cuban doctors stationed in Venezuela describing how they had worked to persuade patients to vote for the country’s ruling Socialist Party, including by refusing treatment for opposition supporters and canvassing on doorsteps with gifts of medicine to bribe waverers.

In response, the Cuban government denied the claims, saying that its “honourable” doctors had saved nearly 1.5m lives in Venezuela, as well as citing their participation in the fight against Ebola in Africa and cholera in Haiti, among other examples.

Carlos also made the move from a Brazilian mission to the US, where he is now rebuilding his life in Houston, working as a medical assistant.

He is now unable to visit Cuba for fear of being imprisoned on the island for desertion. In 2018 he applied for a humanitarian visa to visit his mother who had cancer. It was denied, and he could not see her before she died. “That’s the way they play it, dangling permissions and gifts in front of you so people play ball. I soon realised our mission was more political than humanitarian.”

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESDayli eventually came to a similar conclusion.

She returned to Cuba in 2014 where she was posted to a hospital without an intensive care unit – a clear sign, she says, that she was out of favour. Later she was suspended from medical practice for alleged absences from work – an allegation she rejects. She says she began to be treated as a dissident, with a state security agent posted outside her house who followed her everywhere. Her family and friends were harassed. Eventually, she could take it no more and is currently visiting relatives in Spain, where she may decide to try and settle.

“I wanted to be a doctor in Cuba but I have given that up now. I don’t want to be a risk to my family. I spoke my mind and this is the consequence. They want soldiers, not doctors.”

You may also be interested in…

Cuba has faced more than 50 years of US sanctions. Now, for the first time, a unique drug developed on the communist island is being tested in New York state. But some American cancer patients are already taking it – by defying the embargo and flying to Havana for treatment.