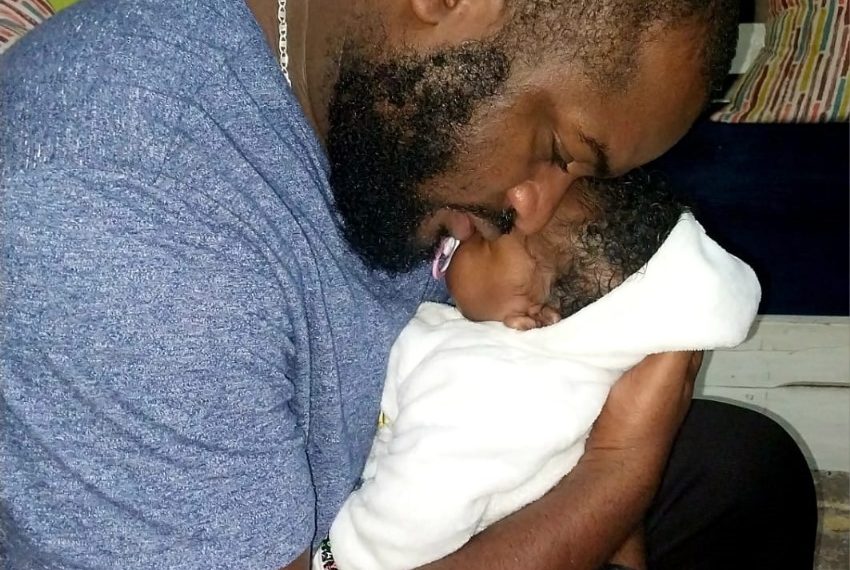

When Brian Odhiambo took his wife, Wendy Majore, to the Hospital in October 2023, he was hopeful and excited to meet their daughter and their first child together, his happiness soon turned sour as a series of events which pointed to delays, resource gaps and what he believed was negligence would soon leave him a Widower.

Majore, a vibrant 25-year-old award-winning designer and former Miss Curvy Kenya 2018, lost life while giving birth due to postpartum hemorrhage (PPH).

“The admitting doctor told me that Wendy had given birth but she was bleeding excessively.” Odhiambo recalls.

According to new guideline released by federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians, PPH occurs when a mother loses 300ml of blood while giving birth and any abnormal vital signs have been observed.

Odhiambo recalls his wife bleeding for forty-five minutes without a transfusion as the hospital waited for him to sign consent forms and mobilize for blood.

“I begged the doctors to save her,” Odhiambo says, “They told me I had to buy four pints of blood at Kshs 5000 each or get eight people to donate, meanwhile she was still bleeding out, how is that possible in a hospital?”

Odhiambo’s story is tragically common as data from the Ministry of Health shows that Kenya loses 15 women every day to preventable maternal deaths, leaving behind a trail of devastation emotionally and financially for the family and society left behind.

Financial Shocks

In Odhiambo’s case as his wife’s situation worsened, so did the financial responsibility, she was taken to the theatre where they repaired her cervix that was torn during childbirth but when the bleeding persisted the medics started asking for a bed at Kenyatta referral Hospital (KNH), when none was available, they told Odhiambo his next option was a private hospital.

“I was asked to raise Ksh 300,000 so that my wife would be transferred to a private hospital” He said “at the same time my newborn was also in distress and needed Oxygen.”

He describes the moment as the point his world fell apart.

“I have no siblings. My mother is ailing and depends on me. I didn’t know where to start.”

Shortly after, Odhiambo’s wife lost the fight, what followed compounded his grief. He was instructed to organize a hearse and identify a morgue. The bill came to Shs 150,000.

The Unpaid Labor of Mothers: The Hidden Economic Cost

Another widower, Victor Ambula understands this pain too well, as he lost his wife Zipporah-his childhood sweetheart to excessive bleeding after delivering their fourth child and first daughter.

“I had no time to grieve they gave me only six hours to figure out how I would evacuate my wife’s body.”

Soon after the burial he had to take home baby Janelle, here the reality hit hard. Baby formula was expensive and reliable child care was hard to find.

“At first my aunt helped, but she eventually had to leave. I had three kids and a newborn. I hired house helps, but I didn’t like how they handled the baby. I had to call my mother to help because I had to work, look for food, pay rent, pay school fees. I couldn’t do it alone.”

The emotional burden also weighed heavily.

“When we split duties, it felt easy. Now I’m alone. I realize every day the unseen work my wife did from managing the house, buying school uniforms before a new school year, homework –everything, it is all harder alone.”

A recent Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) 2025 report titled ‘Economic Value of Unpaid Domestic and Care Work in Kenya’ highlights the significant value of the unpaid labor Kenyan women provide, valued at approximately Kshs 2.54 trillion, representing 23.1 per cent of the country’s GDP and for families like Ambula this had to be replaced with paid caregivers, which proved expensive and unreliable.

The Division of Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (RMNCH) at the Ministry of Health, who reports that an investment of Kshs 1 maternal health yields a six-fold return in economic value for the country.

Mary Magumba, the Advocacy and Communication Program Lead at RMNCH conquers on the value of investing in maternal care and avert preventable deaths like Zipporah’s.

“If you look at the return on investment it’s significant, if we invest early in strong interventions, the country saves.” she said. “If the cost of certain interventions is around 130 shillings per mother, the economic value saved is about 910 shillings annually. Without these interventions, we lose more in lives and in money.”

Newborns are heavily reliant on their mothers, if a mother dies the newborn’s chances of survival reduces significantly.

Currently Kenya loses 92 newborns everyday according to data from the Ministry of Health, these stark numbers show the urgent need for significant investment in MNCH.

Evidence from the World Health Organization (WHO) shows that maternal death increases the risk of neonatal death by up to 20 times, creating further economic and social losses for families and the healthcare system.

“When you lose a mother, the survival of the newborn is also threatened because that baby depends on the mother for breastfeeding and care. The indirect losses are even greater than the monetary ones.” Magumba added.

Research shows that an investment in robust primary healthcare system has a high return on investment, with every dollar invested giving a return of up to USD 16 over a five-year period.

A well-resourced healthcare system is linked to positive economic benefits and accelerated economic growth.

The cost of inaction

In response to the high numbers of maternal mortality, the Ministry of Health says its efforts align with the global ‘Every Woman Every Newborn Everywhere (EWENE)’ approach, which emphasizes universal access to quality maternal and newborn care.

According to the Ministry the full implementation of the Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child, Adolescent Health and Nutrition (RMNCAH-N) Investment would help the country achieve 90 per cent coverage of essential maternal and newborn health.

To achieve EWENE goals, Kenya needs to invest Kshs 32 billion in 2025 and 48 billion by 2030.

This is especially critical if the country hopes to meet its Global Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 2030 of reducing maternal mortality to less than 70 per 100,000 live births from the current 355 per 100,000 live births and Neonatal mortality to 12 per 1000 live births from the current 21 per 1000 live births.

These ambitions greatly clash with reality as healthcare remains grossly underfunded.

In the current financial year budget 2025/26, health was allocated approximately 3.3 per cent (Kshs 138.1B) of Kenya’s total national budget, way below the proposed 15 per cent proposed in the 2001 Abuja Declaration in which Kenya is a signatory.

The maternal mortality data is still high as every day, 15 more women step into hospitals across Kenya and never return to their families.