Kenyan scientists are expanding a nationwide molecular surveillance system to detect early signs of malaria drug resistance as genetic mutations linked to reduced treatment effectiveness are identified in parts of the country.

Researchers at the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme in Kilifi, working with the Ministry of Health and the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP), have identified four key anti-malarial resistance mutations circulating in western Kenya, particularly in eight counties surrounding Lake Victoria.

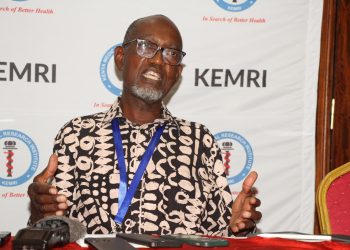

Professor Isabella Oyier, Head of the Biosciences Department at KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Program (KWTRP), is working on a program focusing on malaria molecular epidemiology with the aim of generating actionable molecular surveillance data to support National Malaria control program surveillance.

The study focuses on integrating malaria molecular into routine malaria diagnosis through a network of sentinel health facilities linked to the National malaria reference to enable early detection and monitoring of parasite genetic mutation associated with resistance to antimalarial drugs.

The data from the sentinel laboratories has flagged out one mutation 675 variant of concern drawing particular attention. The same mutation has previously been reported in Uganda, where it has been associated with delayed clearance of malaria parasites following treatment with artemisinin based drugs.

“When parasites are not cleared by day three of treatment, that raises concerns about reduced drug susceptibility,” said Prof Oyier.

Kenya currently uses artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), including Coartem, as the first-line treatment for uncomplicated malaria. ACTs have played a central role in reducing malaria deaths across Africa over the past two decades.

Prof Oyier said the newly detected mutations do not yet signal confirmed treatment failure. Instead, they serve as an early warning.

To strengthen that warning system, scientists are integrating malaria molecular surveillance into routine diagnosis through a network of sentinel health facilities across 8 malaria-endemic counties. The facilities are linked to the National Malaria Reference Laboratory and supported by research laboratories using next-generation sequencing technology.

The system analyzes routine patient samples to detect genetic markers associated with resistance to both anti-malarial drugs and diagnostics. The surveillance data are regularly shared with the NMCP to track resistance frequency and temporal trends.

“Genomic surveillance tells us the mutations are present,” Oyier said. “Therapeutic efficacy trials tell us whether those mutations are actually affecting patient outcomes.”

The World Health Organization recommends that malaria-endemic countries conduct therapeutic efficacy trials every two years to assess whether first- and second-line drugs remain effective under real-world conditions. In these trials, patients are treated and monitored to confirm whether parasites are cleared within three days — a key benchmark for artemisinin effectiveness.

Beyond drug resistance, scientists are also monitoring for mutations linked to diagnostic resistance, particularly deletions affecting histidine-rich protein 2 (HRP2), which could undermine some rapid diagnostic tests. Such diagnostic resistance has already been documented in parts of the Horn of Africa.

Researchers say Kenya’s rapid diagnostic tests and microscopy remain effective. The resistance mutations identified so far relate primarily to drug response rather than diagnostic failure.

Malaria parasites mutate naturally as they replicate. Most mutations are harmless. But when a mutation provides a survival advantage — such as resistance to a drug — it can spread through natural selection, becoming more prevalent over time.

Western Kenya remains one of the country’s highest malaria transmission regions, making it a critical focus for surveillance. Scientists are also analyzing the complexity of infection — measuring how many genetically distinct parasites are present in a single patient — and conducting whole-genome analyses to map Kenya’s parasite population structure.

Health authorities say early detection is essential to prevent widespread treatment failure and to preserve the effectiveness of existing medicines.

Drug quality oversight remains the responsibility of Kenya’s Pharmacy and Poisons Board, which tests medicines entering the market. Therapeutic efficacy trials, meanwhile, assess how those medicines perform in clinical settings.

For now, Kenya’s first-line treatments remain effective, Prof Oyier said, however advising that sustained malaria molecular monitoring is critical.

“Malaria parasites are constantly evolving,” Oyier said. “The goal is to detect resistance early and respond before treatment failure becomes widespread.”

Malaria remains one of Kenya’s leading causes of illness, particularly among children in high-transmission areas. Officials say a robust molecular surveillance platform could serve as a long-term early warning system, guiding targeted interventions and evidence-based treatment policy decisions.